A gaggle of neighborhood women, fellow-Sicilians, peck at her with glee. (She lost the baby, too.) She barely leaves the house, and, when she does, she wears only a slip, like a tart, or a lunatic. Three years later, she is still deranged by mourning. This is the end of Rosario’s life, and also, apparently, of Serafina’s. Fervently devoted to Rosario, she brims with pride and gladness: she is pregnant, but, before she can tell her husband the news, he crashes on the road. This, along with the suspicious appearance of a lanky blonde (Tina Benko), should worry Serafina (Marisa Tomei), but nothing seems to. (Mark Wendland, the set designer, has bordered the stage with sand and loosed on it a flock of plastic flamingos.) Rosario, whom we never see, drives a banana truck, with “something extra” hidden under his cargo-drugs, we gather. The delle Roses live in a Gulf town that is imbued, according to Williams’s production notes, with a gaudy, tropical brightness.

You can almost smell them, sweet, heavy, and verging on rotten.

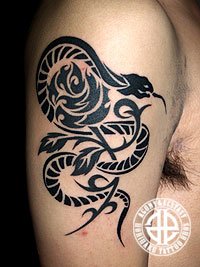

Roses are everywhere-in Serafina’s name and the names of her daughter, Rosa, and her husband, Rosario, who combs rose oil into his hair and bears the titular tattoo on his chest. Before “The Rose Tattoo” reaches toward ecstasy, it wallows in despair there is a wanton, operatic hysteria to the play and to its heroine, Serafina delle Rose, a Sicilian-immigrant seamstress with the soul of a diva. Domestic joy was not a natural subject for him. Williams-who, as a child, was smothered by his grandiose mother and tormented by his seething, frequently absent father-revered, craved, and feared love. Instant attraction, comic hazard, the providential abundance of a happy home: these are also themes in “The Rose Tattoo,” now in a Roundabout Theatre Company revival, directed by Trip Cullman (at the American Airlines).īut those aren’t the only themes. The next day, Williams tells us, he came home to find “little Frankie” asleep “on the huge bed,” the picture of cozy devotion. In his memoirs, Williams, “too long accustomed to transitory attachments,” recalls his initial reluctance to commit and his subsequent realization that, with Merlo, contentment could finally be his. Merlo, a Sicilian-American, first entered Williams’s life as a conquest in Provincetown some years later, a chance encounter on a Manhattan street brought him back into it, more or less for good. Williams wrote the play in a swoon of romantic gratitude for his great love, Frank Merlo. “My love-play to the world,” Tennessee Williams called “The Rose Tattoo,” which was first mounted on Broadway in 1951-the production made Maureen Stapleton a star-and was later adapted into a film with an Academy Award-winning performance by the larger-than-life Anna Magnani.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)